This X-Force IRIS report identifies and analyzes two examples of those BEC scams. Although BEC scams are not new, the examples described here detail how attackers used stolen email credentials and sophisticated social engineering tactics without compromising the corporate network to defraud a company. The objective of this report is to inform customers of the BEC threat by exposing the specific tactics used to deceive victims and offer recommendations that companies can immediately implement to help reduce the risk of falling prey to BEC scams.

The Cyber Con Artist

Business email compromise scams involve taking over or impersonating a trusted user’s email account to target companies that conduct international wire transfers with the goal of diverting payments to an attacker-controlled account.

These attacks are almost entirely based on phishing and social engineering, and are thus attractive to cybercriminals due to their relative simplicity. In most cases, BEC scams involve little to no technical knowledge, malware or special tools.

A recent report by Trend Micro predicted that BEC attacks will comprise over $9 billion in losses in 2018, up from $5.3 billion at the end of 2016. According to the FBI, BEC scams have been reported in every U.S. state and across 131 nations, and have resulted in high-profile arrests.

Attack Summary

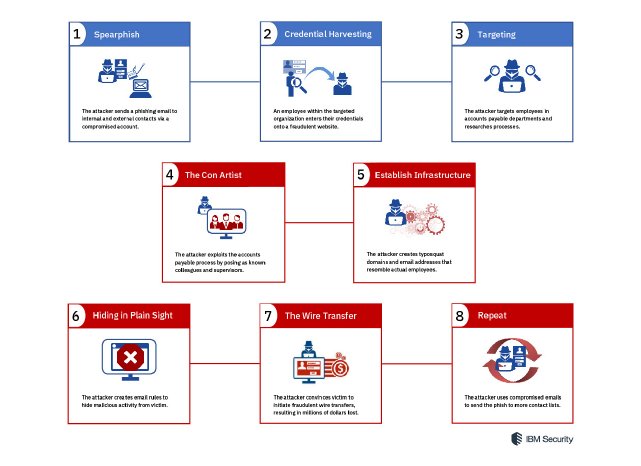

X-Force IRIS researchers observed the attackers involved in BEC scams using well-crafted social engineering tactics that leverage phishing emails to obtain legitimate credentials and ultimately steal large amounts of money.

The following tactics were common to the attacks examined by X-Force IRIS researchers:

- Phishing emails were sent either directly from or spoofed to appear to be from known contacts in the target employee’s address book.

- Attackers mimicked previous conversations or inserted themselves into current conversations between business email users.

- Attackers masqueraded as a known contact from a known vendor or associated company and requested that wire payments be sent to an “updated” bank account number or beneficiary.

- Attackers created mail filters to ensure that communications were conducted only between the attacker and victim and, in some cases, to monitor a compromised user’s inbox.

- In cases in which additional approval or paperwork was needed, the attackers found and filled out appropriate forms and spoofed supervisor emails to get required approvals.

- Without the use of any malware, and with legitimate stakeholders performing the actual transactions, traditional detection tools and spam filters failed to identify evidence of a compromise.

X-Force IRIS assesses that the threat groups that conduct these attacks are likely operating out of Nigeria because both the spoofed sender email addresses and IP addresses used to log in to email web access portals are primarily traced to Nigeria. However, it is worth noting that the same threat actors often leveraged compromised servers or revolving proxies that may be traced to other countries to mask their actual location.

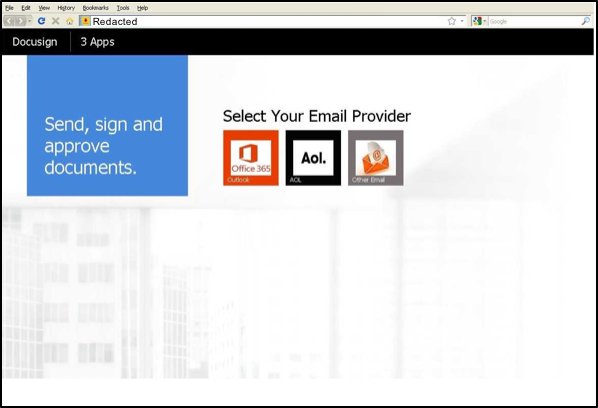

Although the size of each individual group is unknown, the threat actors appear to have used a phishing kit to create spoofed DocuSign login pages on over 100 compromised websites. This indicates that the groups comprise more than one person each and are actively engaged in widespread phishing campaigns to harvest business user credentials.

The compromised websites vary in geographic location, IP address resolution and industry, and did not appear to have any relation to one another. X-Force IRIS researchers have identified targeted companies in at least the retail, healthcare, financial and professional services industries, including Fortune 500 companies.

Setting Up the Hook

The BEC scams identified by IBM incident responders consist of two separate but connected goals. The first is to harvest mass amounts of business user credentials, and the second is to use these credentials to impersonate their rightful owners and ultimately trick employees into diverting fund transfers to bank accounts the attackers control.

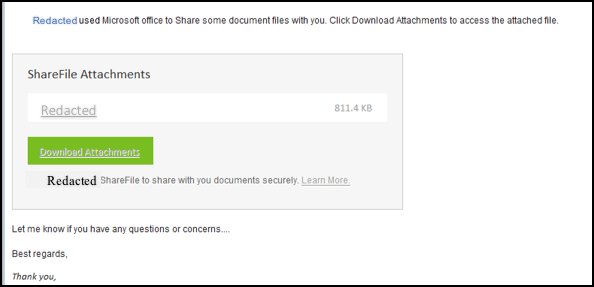

To achieve the first goal, the attackers used credential sets they had already compromised to send a mass phishing email to the user’s internal and external contacts. The phish was often sent to several hundred contacts at a time and was engineered to look legitimate to the spammed contacts.

The attacker used publicly available company information to craft a believable phish containing a link purported to lead to a business document.

If the victim clicked the link, he or she was redirected to a fraudulent “DocuSign” portal requesting the user to authenticate via his or her email provider to download the referenced document.

Neither the email nor the fraudulent “DocuSign” portals contain malware that is downloaded onto the user’s machine.

To accomplish the second goal, the attackers focused on stolen credentials from companies that use single-factor authentication and an email web portal. For example, companies that only require a username and password for employees to access their Microsoft Office 365 accounts were compromised. Using email web portals ensured the attackers’ ability to complete these attacks online and without compromising the victim’s corporate network. The attackers specifically targeted personnel involved in the organization’s accounts payable departments to ensure that the victim had access to the company’s bank accounts.

Before engaging with any employee, the attackers likely undertook a reconnaissance phase, looking through activity within the user’s email folders in search of subjects and opportunities to exploit and, eventually, creating or inserting themselves into relevant conversations.

Sophisticated Social Engineering Tactics

To successfully scam companies without special tools or malware, the attackers used sophisticated social engineering tactics that prey on flaws in common accounts payable processes. X-Force IRIS assesses that the attackers carefully chose to impersonate vendors or associated companies with established relations to the client and target specific people in the organizational chart to increase the believability of the scam.

According to X-Force IRIS incident responders, the attackers typically took a week between the point at which they gained initial access to a user’s email account and the time they started setting up the infrastructure to prepare a credible ruse.

During this time, they likely conducted extensive research on the target’s organizational structure, specifically focusing on the finance department’s processes and vendors. The attackers also revitalized previous conversations with accounts payable personnel to learn any company-specific wire payment policies.

The attackers’ thoroughness during reconnaissance and while financial conversations took place involved actions such as impersonating victims, finding and spoofing internal documents needed to make legitimate wire transfers, and setting up multiple domains and emails to pose as higher-level authorities.

The attackers sent communications to targets directly from a compromised email address. To keep the victim unaware of the communications, the attackers created email rules to filter the emails out of the victim’s inbox. In other instances, the attackers used a typo-changed email address in the “reply to” field so the compromised user would not receive responses. If the receiver did not scrutinize the “reply-to” field, which often requires expanding the email header, the email would otherwise appear to come from a legitimate contact.

The attackers also set up domains similar to the target company’s vendors, albeit with a hard-to-identify typo change — for example, doubling a letter of the company name in the URL or registering the vendor’s name with a different top-level domain (TLD), such as .net instead of .com. The domain names were then used to set up email accounts purporting to belong to known employees, and emails from those accounts were sent directly to the targets.

In one example, the attackers registered a new domain to send fake approval messages impersonating different levels of the supervisory chain, including copying email signatures of the relevant business executives.

Finally, although the attackers made some grammatical and colloquial mistakes, their English skills were proficient and the few mistakes they made could be easily overlooked by the target. The attackers created a false sense of reality around the target and imparted a sense of urgency to pay, resulting in successful scams involving millions of dollars.

Hiding in Plain Sight

Since the attackers conducted correspondence from a victim user’s email, they created email rules to keep the victim unaware of the compromise. In cases in which the attackers impersonated the user, the attackers auto-deleted all emails delivered from within the user’s company. They likely did this to prevent the user from seeing any fraudulent correspondence or unusual messages in his or her inbox. Additionally, the attacker auto-forwarded email responses to a different email to read the responses without logging in to the compromised account.

Separately, when attackers used stolen credentials to send mass phishing emails, they simultaneously set up an email rule to filter all responses to the phish, undelivered messages, or messages containing words such as “hacked” or “email” to the user’s RSS feeds folder and marked them as read.

Follow the Money

X-Force IRIS incident responders noted that the threat actors had more financial success using shell corporations and corresponding bank accounts based in Hong Kong or China rather than using consumer bank accounts, in which cases financial institutions were more likely to delay or block large or unusual transactions.

According to X-Force IRIS analysis, the shell corporations involved in the BEC scams were registered within the past year, some as recently as the same month that payments were requested to the account. According to the FBI, banks located in China and Hong Kong are the primary destinations for fraudulent wire transfers associated with BEC scams.

Recommendations for Preventing Business Email Compromise Attacks

Attackers are constantly honing their craft to create more believable scams and increase the difficulty in identifying falsified emails. Simply training employees on phishing threats and BEC scams is not always sufficient. Implementing key security features and revisiting internal processes can help reduce the risk of being targeted by a low-tech social engineering campaign.

- Implement two-factor authentication (2FA) for account logins. Multifactor authentication (MFA) limits the ability of scammers to use stolen credentials obtained through mass phishing and spoofed login pages alone.

- Create banners that identify emails coming from external email addresses. Easily identifiable banners could allow employees to instantly judge whether an email has been spoofed, even when the typo is hard to discover from sight alone.

- Block the ability to auto-forward emails outside of the organization: An auto-forward block would prevent an attacker from forwarding emails to an alternate email account and force the attacker to log in to the victim’s account with stolen credentials, increasing the likelihood that the victim observes suspicious activity.

- Implement strict international wire transfer policies.Employees involved in financial transactions should receive role-based training with ample information about BEC scams. Those with account access should be required to use digital certificates to validate the legitimacy of emails they receive. In addition, setting an obligatory time delay requirement for overseas transactions can reduce the ability of attackers to impart a sense of urgency and trigger the employee into hasty action.

- Verify the vendor. If something does not seem right, an account has been changed or the wire amount is higher than typically requested, employees should call the vendor using a validated phone number. Having to obtain sign-off in person or over the phone from the employee supposedly requesting the transfer/change of account can help organizations stop a fraudulent wire before it occurs.