As the Covid-19 pandemic threw global markets into disarray, consumer behavior changed dramatically, leaving the carriers as well as shippers stranded, either with goods they could not sell, or, in the second half of the year, with goods that cannot be moved.

The latter crisis stems in part from a lack of containers, as the pandemic has caused box repositioning problems. Today, even if a beneficial cargo owner (BCO) can get an empty container for their cargo, there is no guarantee that the cargo will make it onto a ship.

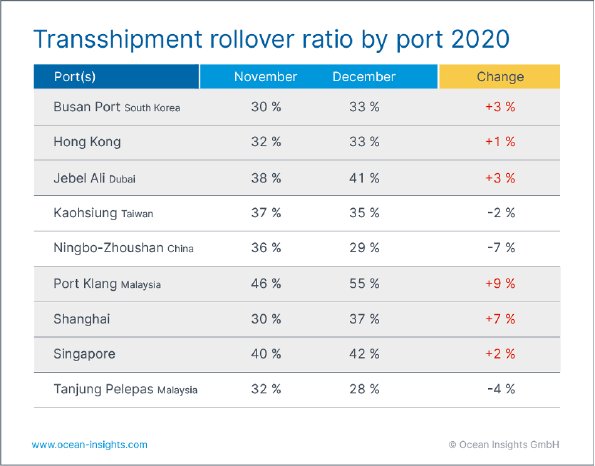

The latest figures from Ocean Insights show that most major ports are seeing elevated levels of rollover cargo from November to December. Rather than cargo flows diminishing in line with historical seasonal precedent, there are growing levels of demand during a period that usually sees a decrease in volumes. This in turn is forcing further delays to cargo, which is increasingly lying stranded at the quayside.

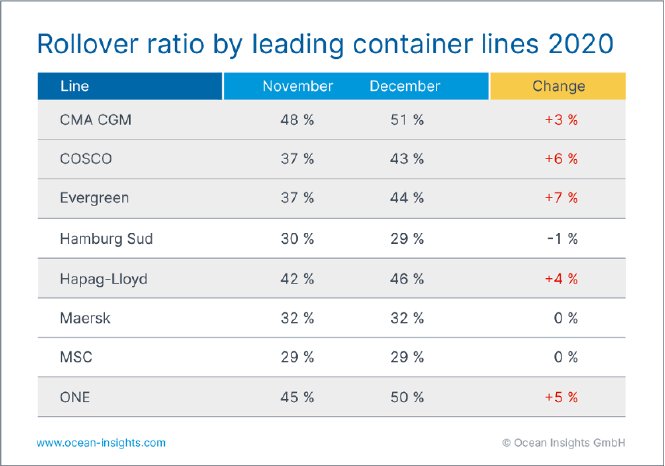

Ocean Insights calculates the rollover ratio for carriers as the percentage of cargo carried by each line globally that left a port on a different vessel than originally scheduled.

“Of the 20 global ports for which Ocean Insights collates data, 75% saw an increase in the levels of rollover cargo in December compared to the previous month. Major transshipment facilities such as Port Klang in Malaysia and Colombo in Sri Lanka recorded 50% or more of cargo delayed, with the world’s largest transshipment hub in Singapore and leading primary ports such as Shanghai and Busan rolling over more than a third of their containers, last month” said Ocean insights’ Chief Operations Officer Josh Brazil.

Industry experts are now warning that the cargo surge could last well into 2021, with a strong likelihood that the prevailing conditions will continue throughout the first half of the year.

Much of the recent concern for rollover cargo has focused on reefer containers. Some ports in China are reported to have run out of power points that are used to supply electricity to reefer containers, jeopardizing perishable cargo.

Port Rollovers:

Overall rollover levels increased to 37% month on month in December, averaged across the ports surveyed, which includes facilities in all the major cargo regions of Europe, the US, and Asia as well as less cargo intensive regions such as Latin America. However, Latin America accounts for a significant proportion of the reefer trade with the US, Asia, and Europe.

While rollover levels can vary considerably from 62% in Italy’s Gioia Tauro, now owned and operated by MSC, to just 22% in Salalah in the Middle East, it is worth noting that Shanghai’s 37% rollover level is likely considerably higher in actual container numbers than Cartagena’s 56% rollover rate.

Meanwhile, the extra loader policy, seen in South Korea’s Busan Port, which saw a 4% reduction in its rollover levels in November, has, for the most part, lost those gains with a 3% increase in December.

“This indicates that the levels of cargo are still rising while the extra loader capacity which has been deployed to meet the raised levels of demand appears to be having little effect,” explained Mr. Brazil.

Unsurprisingly, the major ocean shipping companies have also seen an overall increase in rollover values from 35% in November to 37% in December. Three of these lines saw more than 50% of cargo left at the departure port.

Alliance partners MSC and Maersk managed to stem the rise of rollover cargo month on month, both recording the same level of rollovers in December as in the previous month.

The one statistical outlier in the pack is the South Korean carrier HMM, which joined the THE Alliance in April and managed to limit its rollover cargoes to less than 30% in all but two of the subsequent months; until December when the previous month’s figure of 23% more than doubled as the carrier saw a 26% increase in cargo rollover, reaching 49% for December.